A 20 year old female patient referred herself to a surgical oncologist specializing in sarcomas after she presented to an outside hospital for a sudden onset of epigastric pain. The patient also reported a one-year history of decreased appetite without nausea, vomiting, or weight loss. The outside institution performed an abdominal ultrasound and identified a large nonvascular heterogenous masslike lesion in the left upper quadrant not definitively associated with the spleen or kidney. The mass measured 12.1 x 9.9 x 10.7 cm. The radiologist’s overall impression was a hematoma; however, a CT scan with contrast was recommended to further classify the lesion. Instead, an MRI was performed, and the same radiologist described the lesion as having a thick irregular enhancing rind with enhancing septations and central necrosis. With the lesion appearing distinct from adjacent organs, a retroperitoneal sarcoma was posited on imaging. Reviewing the outside imaging and clinical history, the surgical oncologist referred the patient to interventional radiology for an ultrasound-guided biopsy of the left-sided retroperitoneal mass.

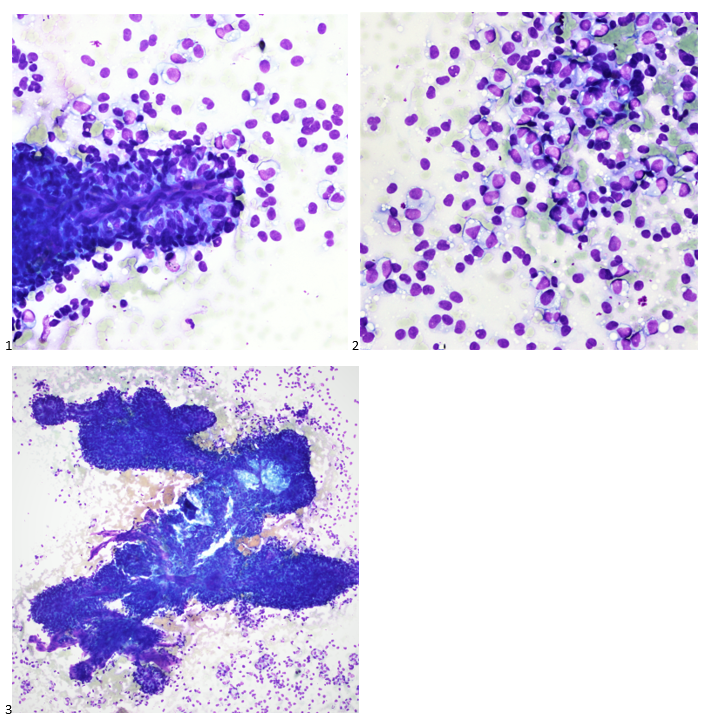

When the cytologist arrived in the procedure room for the time-out, the radiologist informed her of the surgical oncologist’s and outside radiologist’s opinions of a retroperitoneal sarcoma. A 17-gauge coaxial needle was advanced into the peripheral and non-necrotic aspect of the retroperitoneal mass, and multiple 22-gauge fine needle aspirations were obtained and handed to the cytologist. She prepared two air-dried smears and two alcohol-fixed slides. The air-dried smears were stained in our Diff-Quik (DQ) set-up and deemed adequate. The pathologist’s immediate cytologic evaluation was “tumor cells present.”

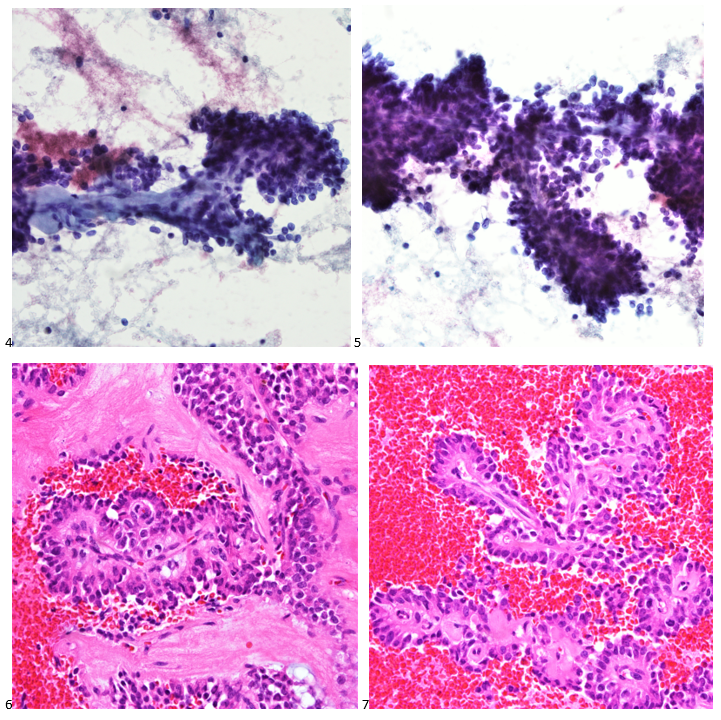

The following morning, the cytologist primary screened the Papanicolaou-stained slides and H&E-stained cell block sections in addition to the DQ smears, with the former preparations presented below.

The cytologist entered her results as positive for malignant cells with a note of “atypical cells in papillary fragments” and gave the case to the pathologist for the final interpretation. The pathologist reviewed the slides prior to ordering immunostains. He paused and thought, “there’s something about the morphology and her age… it just doesn’t make sense for this to be a retroperitoneal sarcoma. It doesn’t look like a sarcoma. The cells are just too round or ovoid, bland, and poorly cohesive, and the fibrovascular cores – I just don’t think this is a sarcoma. Maybe a melanoma? Or some type of renal tumor? The cytoplasmic vacuolization could suggest this, but the mass is distinct from the kidney, so it can’t be. The nuclear grooves are intriguing, almost like a papillary thyroid carcinoma. A neuroendocrine tumor is also possible, the delicate papillary fronds though… Hmm. But where would it be originating from? How could this be distinct from other organs in the abdominal cavity?” He hemmed and hawed, glancing over our list of in-house immunostains. With only nine pre-cut unstained sections associated with the three H&E cell block levels, the pathologist ordered additional unstained recuts. He knew this was going to be a challenge due to the discrepancy between the clinical history and the morphology.

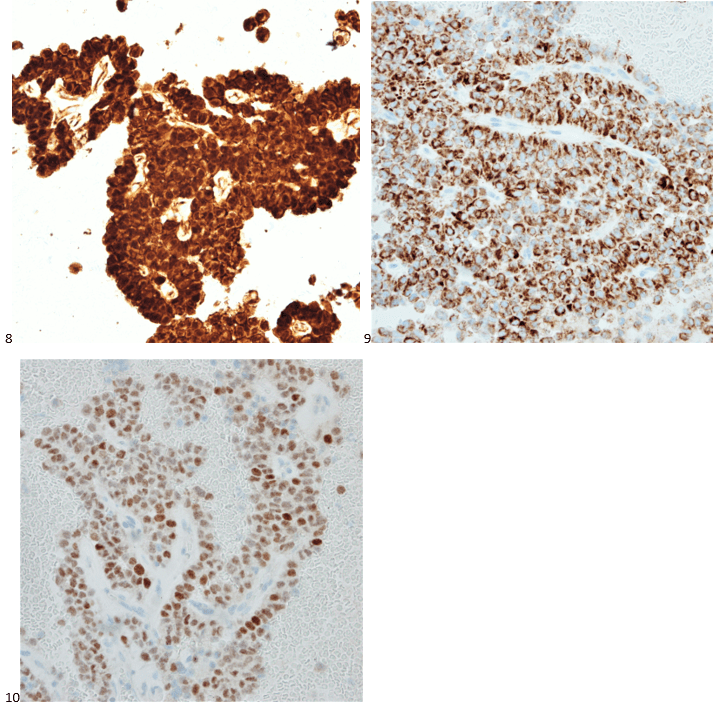

With proper positive and negative controls, the tumor cells show positive staining for AE1/AE3, Cam 5.2, vimentin, CD99 (dot-like), CD56, beta catenin (nuclear), PR, AMACR, and SOX11, while negative staining for CK7, CK20, PAX-8, RCC, chromogranin, synaptophysin, GATA-3, EMA, GFAP, S100, calretinin, WT-1, E-cadherin, and p53 (wild type pattern). The proliferative index by Ki-67 is low at <1%.

The combination of morphology with the extensive immunoprofile of the tumor is consistent with solid pseudopapillary neoplasm (SPN) of the pancreas.

Had there been any mention of the tumor involving or replacing the pancreas, this diagnosis and workup would have been much more straightforward. SPNs, albeit rare, account for 30% of tumors in women within their third or fourth decade of life.1 This patient presented with the most common SPN symptoms of abdominal pain and early satiety, but the mass appearing extrapancreatic on imaging posed a diagnostic challenge, as extrapancreatic SPNs are rare.2-3 Fortunately, SPNs are low-grade malignant neoplasms that respond well to surgical resection, and this patient is doing just fine after her distal pancreatectomy. In this case, both the patient and our pathologist listened to their guts with the patient pursuing advanced medical care for something much more complicated than a hematoma and the pathologist relying on his morphology expertise despite an odd clinical presentation.

References

- La Rosa S, Bongiovanni M. Pancreatic solid pseudopapillary neoplasm: key pathologic and genetic features. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. 2020;144(7):829-837. doi:10.5858/arpa.2019-0473-ra

- Dinarvand P, Lai J. Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas: a rare entity with unique features. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. 2017;141(7):990-995. doi:10.5858/arpa.2016-0322-rs

- Cheuk W, Beavon I, Chui D, Chan JKC. Extrapancreatic solid pseudopapillary neoplasm. International Journal of Gynecological Pathology. 2011;30(6):539-543. doi:10.1097/pgp.0b013e31821724fb

-Taryn Waraksa-Deutsch, MS, SCT(ASCP)CM, CT(IAC), has worked as a cytotechnologist at Fox Chase Cancer Center, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, since earning her master’s degree from Thomas Jefferson University in 2014. She is an ASCP board-certified Specialist in Cytotechnology with an additional certification by the International Academy of Cytology (IAC). She is also a 2020 ASCP 40 Under Forty Honoree.