Case Presentation

A 74 year old male presented to UVMMC for a routine sputum culture at the adult cystic fibrosis (CF) clinic. At this visit, there were no pulmonary complaints, but chest imaging indicated scarring and atelectasis of the right upper lung and left mid lung. The imaging did not show signs of pulmonary infection.

The patient’s initial diagnosis of CF occurred at age 69 after a history of recurrent respiratory infections, bronchiectasis, and infertility. An elevated sweat chloride confirmed a CF diagnosis and subsequent genetic testing showed heterozygosity for 2 disease-causing CFTR mutations: p. Leu206Trp and p. Phe508del. Additional relevant medical history includes a history of smoking and ongoing pancreatic issues likely related to CF. The patient has been prescribed elexacaftor/texacaftor/ivacaftor which seems to be improving his pulmonary symptoms, as well as supplemental pancreatic enzymes which have moderately improved his pancreatic symptoms. Routine sputum cultures are often performed in CF patients to monitor treatment and disease progression, as well as detect any possible latent infections.6 A culture from this same patient in 2022 indicated an infection with Pseudomonas fluorescens, highlighting the importance of routine disease monitoring in CF patients.

Laboratory Workup

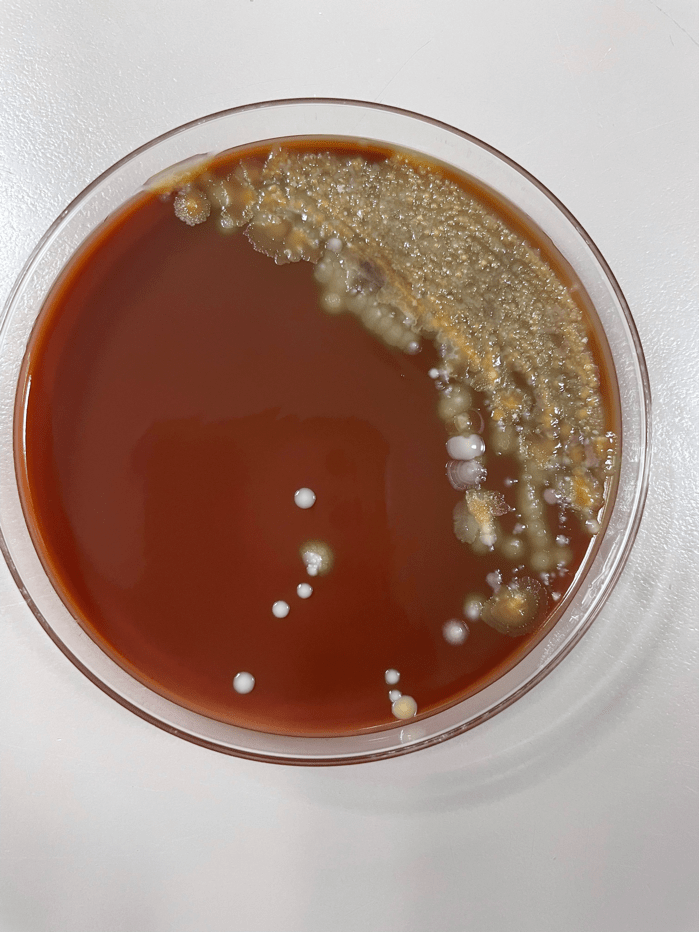

The sputum sample taken from the patient was routinely processed and planted to blood, chocolate, MacConkey, CNA, and Burkholderia cepacian agars. Growth from both the blood agar plate and the chocolate agar plate contained an organism with mucoid morphology, in addition to normal oropharyngeal flora. After subbing out these mucoid colonies, organism growth was observed on both a blood agar plate and a MacConkey medium plate. Growth from the MacConkey agar plate indicated the organism was a non-lactose fermenter, as observed in the un-pigmented colonies and the agar itself remaining a pink color.3 The mucoid organism was determined to be a mucoid strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from MALDI-ToF.

Discussion

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is an autosomal recessive disease with the potential to affect multiple organ systems including the respiratory, digestive, and reproductive systems.7 The primary cause for this disease stems from mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene, of which more than two thousand different mutations have been described.1 In healthy individuals, this gene is responsible for the production of a protein that transports salts across different bodily tissues, yet mutated versions of this gene produce proteins that are absent or dysfunctional, and thus cannot promote salt transport and water movement as efficiently.2 The various mutations of the CFTR gene can result in numerous types of clinical presentations, but these mutations are most often observed to impact mucus viscosity with thick, sticky mucous along with chronic respiratory infections considered a hallmark of this disease.7 Further, decades of research have described additional manifestations of CF, including infertility, chronic sinusitis, and pancreatic damage, as well as an increased risk for dehydration.2

The most commonly performed diagnostic test for CF patients includes a sweat chloride test, for which a sweat chloride concentration above 60 mmol/L is indicative of a CF diagnosis and results directly from the loss of function of the CFTR proteins.1 Since the first descriptions of CF in 1935,1 newborn screening programs have been implemented with the hopes of catching potential cases early and improving prognoses. The newborn test screenings are often focused on the detection of immunoreactive trypsinogen in the blood, as the levels of this chemical are often elevated in patients with CF.1

Further, DNA analysis has proven to be an extremely useful tool in the diagnosis of CF patients, but these analyses are limited to the detection of only the most common mutations and can misdiagnose some of the rare variants of the disease.7 Additionally, because there is a wide range of disease-causing genotypes resulting in CF, some patients may exhibit a late onset of symptoms while still having two CFTR mutations, accounting for the increase of diagnoses made during adulthood.1 This would explain why the patient, in this case, may have been diagnosed so late in life; with two separate gene mutations, the patient may not have exhibited the classical symptoms of CF earlier in life.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a common pathogen found in CF patients and contributes significantly to patient morbidity and mortality.4 P. aeruginosa, upon infection of the lung, promotes the accelerated decline of pulmonary function in CF patients and has been shown to exhibit significant resistance to both the innate immune system and antibiotics through the expression of specific virulence factors.5 Because CF patients are susceptible to chronic lung infections, repeat treatment with antibiotics has also been shown to promote adaptive mutations to P. aeruginosa, making this pathogen a particularly dangerous organism for CF patients.5 The versatility of the organism makes it capable of causing both acute and chronic infections, and the persistence of P. aeruginosa within CF patient airways into adulthood can be explained by the complex relationship between the organism’s pathogen traits and various host factors.4

Because P. aeruginosa has a reputation for being especially resistant to antibiotics, it is especially difficult to treat in CF patients who are routinely treated for chronic infections. The best treatment course would be to conduct an antibiotic resistance panel from the sputum culture sample to determine which of the available antibiotics might have the greatest treatment response against the bacteria.

References

1 De Boeck K. (2020). Cystic fibrosis in the year 2020: A disease with a new face. Acta paediatrica (Oslo, Norway : 1992), 109(5), 893–899. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.15155

2 Endres, T. M., & Konstan, M. W. (2022). What Is Cystic Fibrosis?. JAMA, 327(2), 191. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.23280

3 Jung, B., Hoilat, G.J., (2022, September) MacConkey Medium. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Accessed on September 26th, 2023, from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557394/

4 Jurado-Martín, I., Sainz-Mejías, M., & McClean, S. (2021). Pseudomonas aeruginosa: An Audacious Pathogen with an Adaptable Arsenal of Virulence Factors. International journal of molecular sciences, 22(6), 3128. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22063128

5 Malhotra, S., Hayes, D., Jr, & Wozniak, D. J. (2019). Cystic Fibrosis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa: the Host-Microbe Interface. Clinical microbiology reviews, 32(3), e00138-18. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00138-18

6 National Guideline Alliance (UK). Cystic Fibrosis: Diagnosis and management. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2017 Oct 25. (NICE Guideline, No. 78.) 9, Pulmonary monitoring, assessment and management. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535669/

7 Radlović N. (2012). Cystic fibrosis. Srpski arhiv za celokupno lekarstvo, 140(3-4), 244–249. Accessed on September 28th, 2023, from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22650116/

-Maggie King is a Masters Student in the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine at the University of Vermont Larner College of Medicine.

-Christi Wojewoda, MD, is the Director of Clinical Microbiology at the University of Vermont Medical Center and an Associate Professor at the University of Vermont.