Case History

A 36 year old male with no past medical history presented to an outside hospital with two weeks of worsening headache, fever, and altered mental status. The patient initially presented to his primary care physician with a headache, for which he received an antibiotic injection. Over the next several days, he developed a fever to 39.4oC, worsening mental status, and bowel incontinence. Once admitted, he experienced an intractable seizure, was subsequently intubated, and transferred to the ICU. CT imaging revealed multiple ring-enhancing lesions throughout the brain, most prominent in the right parietal lobe. Additionally, he was found to have a new diagnosis of HIV (CD4 count 40). He was transferred to our institution for a higher level of care but experienced a rapid progression of disease with deterioration of brainstem reflexes and marked cerebral edema, prompting a brain biopsy.

Laboratory Identification

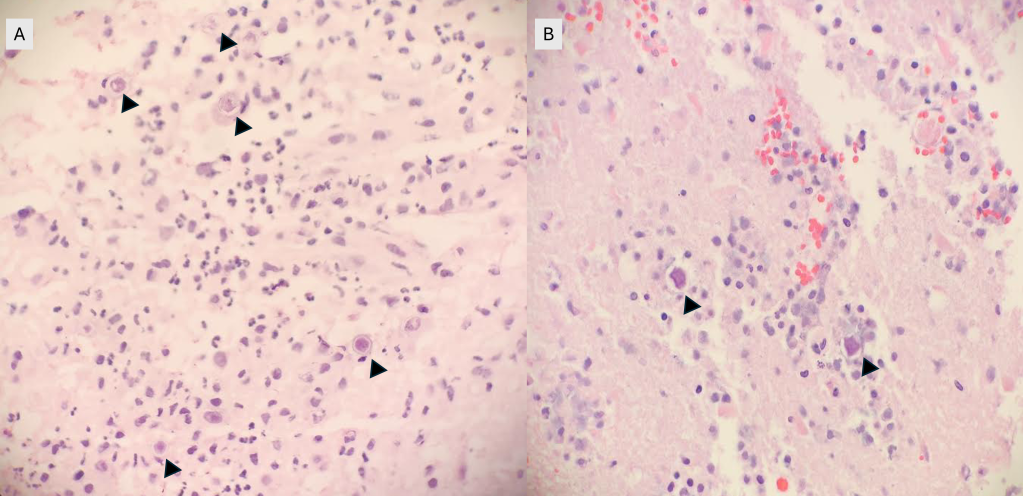

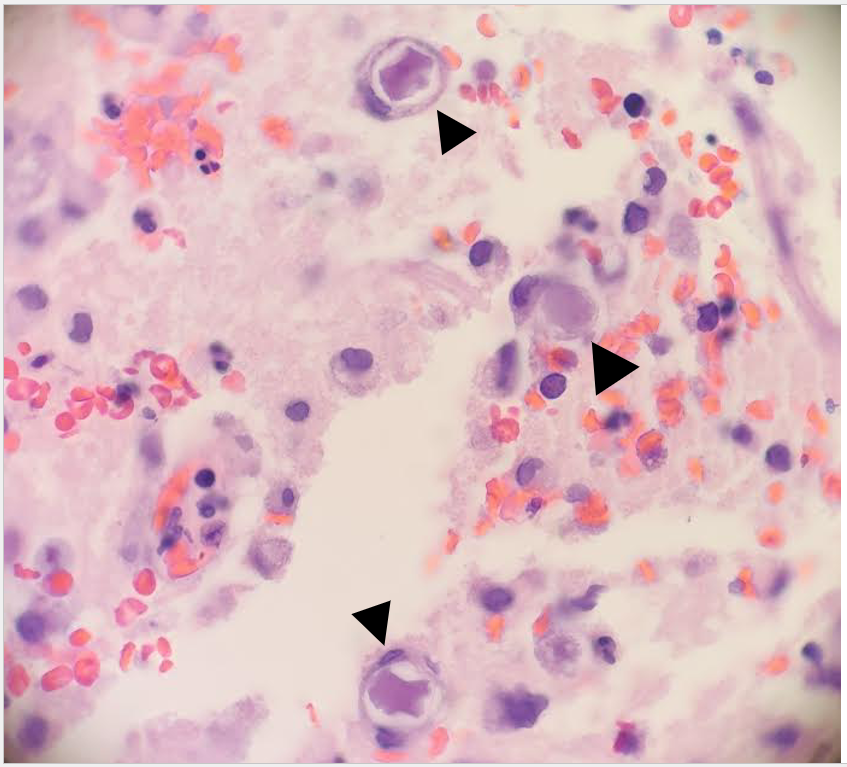

Frozen and permanent sections of a right temporal biopsy revealed frankly necrotic brain tissue with amoebic cysts and trophozoites, consistent with free-living amoeba (Figure 1 and 2). Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) cytology was unremarkable. A specific immunohistochemistry (IHC) assay for Acanthamoeba species was performed at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC; Atlanta, GA), confirming the diagnosis of granulomatous amoebic encephalitis from Acanthamoeba.

Discussion

Acanthamoeba are free-living amoebae found worldwide in a variety of environmental sites, including soil, water, sewage, swimming pools, contaminated contact lens solution, and heating, ventilating, and air conditioning systems.1,2 The Acanthamoeba lifecycle consists of two stages: cysts and trophozoites. Although trophozoites represent the infective form, both cysts and trophozoites can enter the body through various means, including the eye, nasal passages, or broken skin.2,3. There are three distinct diseases that can be caused by Acanthamoeba: Acanthamoeba keratitis, disseminated infection, and Granulomatous Amebic Encephalitis (GAE).1

GAE is a parenchymal disease that occurs when Acanthamoeba enters the body through the respiratory system or broken skin, spreads hematogenously, and invades the central nervous system.2,3. Risk factors include immunocompromised status, such as HIV/AIDS, history of organ transplant, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, liver cirrhosis, and malignancy.1,3 The clinical course tends to be subacute to chronic, with progressive neurological decompensation over weeks to months and eventual death. Imaging may reveal ring-enhancing lesions, arterial occlusions, infarctions, ventricular shifts, and areas of abnormal enhancement.3 CSF analyses may show a pleocytosis with lymphocyte predominance, increased protein, and decreased glucose; amoebae are typically not identified.3. While microscopic evidence of double-walled cysts and/or trophozoites demonstrates the presence of free-living amoeba in infected tissues, diagnosis of Acanthamoeba must be confirmed via specific IHC assays or PCR-based molecular techniques.4

There is currently no standardized recommended treatment, and no single agent has been shown to be universally effective.3. Rare successful cases have involved prolonged therapy using combinations of pentamidine isethionate, sulfadiazine, amphotericin D, azithromycin, flucytosine, and fluconazole or itraconazole.3,5

The patient was treated with miltefosine, fluconazole, pentamidine, flucytosine, and sulfadiazine, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim and azithromycin for HIV prophylaxis, and levetiracetam for seizure prophylaxis. Though repeat MRI of the brain/brain stem showed interval improvement of disease burden, he remained unresponsive to verbal, tactile, and painful stimuli, and his overall prognosis remained guarded. The patient was discharged to a long-term acute care facility, but returned to the emergency department one week later with recurrent seizures, hypotension, and fevers. Imaging revealed new areas of restricted diffusion in the right occipital and left parietal lobes. Despite continued treatment, the patient continued to decline and died approximately three months following his initial diagnosis.

References

1 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parasites – Acanthamoeba – Granulomatous Amebic Encephalitis (GAE); Keratitis. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/acanthamoeba/index.html. Accessed April 24, 2024.

2 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. DPDx- Free Living Amebic Infections. https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/freeLivingAmebic/index.html. Accessed April 24, 2024.

3 Siddiqui R, Khan NA. Biology and pathogenesis of Acanthamoeba. Parasit Vectors. 2012 Jan 10;5:6. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-6. PMID: 22229971; PMCID: PMC3284432.

4 Haldar SN, Banerjee K, Modak D, Mondal A, Sharma C, Vasireddy T, Karad RK, Patel HB, Majumdar D, Bhattacharjee B, Khurana S, Ghosh T, Guha SK, Saha B. Case Report: A Series of Three Meningoencephalitis Cases Caused by Acanthamoeba spp. from Eastern India. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2024 Jan 9;110(2):246-249. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.23-0396. PMID: 38190743; PMCID: PMC10859797.

5 Visvesvara GS, Moura H, Schuster FL. Pathogenic and opportunistic free-living amoebae: Acanthamoeba spp., Balamuthia mandrillaris, Naegleria fowleri, and Sappinia diploidea. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2007 Jun;50(1):1-26. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2007.00232.x. Epub 2007 Apr 11. PMID: 17428307.

-Cristine Kahlow, MD, Pathology PGY-1 at UTSW Medical Center

-Clare McCormick-Baw, MD, PhD is an Assistant Professor of Clinical Microbiology at UT Southwestern in Dallas, Texas. She has a passion for teaching about laboratory medicine in general and the best uses of the microbiology lab in particular.

-Andrew Clark, PhD, D(ABMM) is an Assistant Professor at UT Southwestern Medical Center in the Department of Pathology, and Associate Director of the Clements University Hospital microbiology laboratory. He completed a CPEP-accredited postdoctoral fellowship in Medical and Public Health Microbiology at National Institutes of Health, and is interested in antimicrobial susceptibility and anaerobe pathophysiology