This post is going to travel slightly off the beaten path by presenting a comparative analysis of my two favorite things – scuba diving and laboratory medicine. What in the world, you say? How can you possibly liken a recreational activity to an entire field of study? Easy. You just have to have a passion for both! I’ve been swimming and snorkeling since I was a wee little kid, always fascinated with being able to free dive down to the bottom of a body of water in one breath (you can blame my mermaid encounter for that). Around that same time, my parents gave me first microscope. The obsession with water was real, always examining wet mounts of everything that could fit between the slide and the coverslip. All throughout my grade school and undergrad years, I flourished in any science course that featured a microscope, finally acknowledging the fact that I had a knack for cells and tissues under the light microscope. During each summer break, I’d travel down to Florida with my parents and embrace the hidden gems of freshwater springs. It wasn’t until my junior year of college where I took a histology course during my summer break that I realized I wanted to make a career of this. During that summer, I began to research scuba diving; however, it wasn’t until after grad school and establishing a career as a cytologist that I finally committed to the idea. 10 years after graduating from a cytology program, I became the cytology supervisor at a renowned cancer center, and six years after my initial scuba diving certification, I became a dive professional, earning the title of divemaster.

Now, you should know that I like to dive deep into things – be it 112 feet down into a dark cavern or fully immersing myself in my work. Here, we’re going to dive into both scuba and the laboratory.

First and foremost, in both fields – diving and laboratory medicine, safety is paramount. There are rules and mechanisms in place to ensure that no one gets hurt. Policies and procedures are designed to keep you, your peers, and your “customers” (patients and students/certified divers) safe. Failure to follow a procedure can jeopardize lives. I’m certain you understand where I’m going with this. There are inherent risks in both fields, and we try to error-proof as best as we can. In diving, safety checks include checking you and your dive buddy’s equipment and configuration to make sure that gas cylinders are turned on and filled to an appropriate pressure, all hoses are connected and work as designed, releases and weights are secured, and that the divers have everything they need to perform the dive. Fortunately, in the laboratory, automation and barcoding has relieved the human eye of some of the burden of solely checking every patient detail, every order, and every equipment’s function. However, laboratory professionals must do their due diligence to double check. No piece of equipment is perfect, but following a procedure designed to avoid errors is the first step in verifying that the correct test has been ordered and the correct results will be delivered to the correct patient.

If you thought that preventative maintenance was necessary for lab equipment, scuba gear is the same way. Unlike a laboratory inspection, diving, for the most part, does not require evidence of gear maintenance to be “compliant” and therefore fit for use. The exception is visual inspection and hydrostatic testing of gas cylinders, but this is more a Department of Transportation rule. With that said, one of the top three reasons for dive accidents is equipment failure due lack of routine maintenance. That’s a risk I’m not willing to take. As much as I wish I had gills, I’m limited to the human form and the environment we are designed to live in. So whether it’s your own life or a family member’s test result, make sure that the relevant equipment is maintained per the manufacturer’s instructions or a more stringent policy or regulation.

One of the many things I practice (while still ensuring a lean mindset) is redundancy. In diving, redundancy comes in the form of equipment. At a minimum, you should have two computers, two flashlights, two air sources, two regulators, two masks, two cutting implements, two people (buddy team), etc. If something goes wrong during a dive, there is a backup that can get you out of jam so that you can safely continue, or if necessary (and more likely the case), end that dive and formulate a plan for future dives. Think of needing to end the dive as a downtime procedure. In the laboratory, redundancy is having two centrifuges, two staining machines, two accessioning workstations, two analyzers (if that’s even in the budget), and other alternative, yet necessary procedures in the event of an electronic or equipment failure. The concept of redundancy is to maintain operations AND safety if something goes wrong.

Lastly, and something that I end my staff huddles or one-on-ones with is personal well-being. In diving, we disclose that it is okay to call a dive at any point for any reason, and a reason does not have to be provided. If you deem yourself physically, emotionally, or mentally unfit for a dive on any given day, call it. Do not muster through and pretend everything will be okay. That’s when divers neglect equipment checks, or fail to watch their gas consumption, depth limits, or time spent underwater. That’s when accidents happen. When you cannot be present for a dive, you cannot be present for your buddy or your students or divers that you are leading. In laboratory medicine, if you are not well, take the day off. I know we are dealing with staffing shortages across the country, I know that it might shift additional work onto a colleague, but you cannot risk jeopardizing patient care because you neglected yourself. Putting on a brave face for others in a world where it’s encouraged to be vulnerable is detrimental to more than just yourself, it’s detrimental to your passions. So take care of yourself and your (buddy) teams so that you can keep your passions safe and productive.

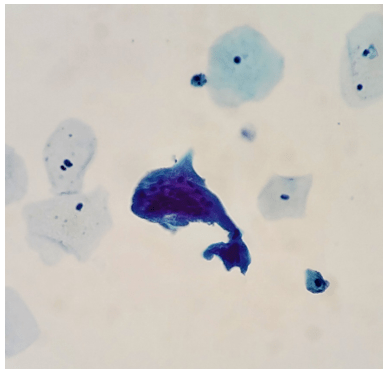

P.S. Sometimes diving and cytology overlap under the microscope, too!

-Taryn Waraksa-Deutsch, DHSc, SCT(ASCP)CM, CMIAC, LSSGB, is the Cytopathology Supervisor at Fox Chase Cancer Center, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She earned her master’s degree from Thomas Jefferson University in 2014 and completed her Doctorate of Health Science from Bay Path University in 2023. Her research interests include change management and continuous improvement methodologies in laboratory medicine. She is an ASCP board-certified Specialist in Cytology with an additional certification by the International Academy of Cytology (IAC). She is also a 2020 ASCP 40 Under Forty Honoree. Outside of her work, Taryn is a certified Divemaster. Scuba diving in freshwater caverns is her favorite way to rest her eyes from the microscope.

I love this deep dive so much thank you for sharing and relating it to our overall well being a message that cannot be shared enough in order for our passions to thrive! I’m sure this provokes many of us with secondary passions to query the relation between them.